When portrayed on the grand scale, villains in fiction can be surprisingly fascinating. Would vampires as a race have gained such worldwide appeal without a sinister undead gentleman in evening dress dominating the screen or the page? Equally, would psychological thrillers be so appealing without a smorgasbord of juicily evil, darkly charming murderers? Hannibal Lecter, let’s remember, could be very courteous if you caught him in the right mood.

Creating a fictional villain is an absorbing exercise, although there are a number of decisions to be made at the outset. All characters need motives, and villains need them more than most characters. They have to have reasons for what they do. Revenge, money, the righting of a wrong. A traumatic event in childhood, perhaps, that’s warped the character’s view of the world.

Even after the motive has been satisfactorily worked out, there’s still a vast embarrassment of riches from which to choose. Is the villain to be an  outright maniac, stalking, Jack-the-Ripper-like, through dark streets, with the accompaniments of swirling cloak and sinister surgeon’s bag? Would it be over the top to have a chuckling, hand-washing Sweeney-Todd character? While acknowledging the irresistible Johnny Depp’s performance in that role, it has to be observed that nobody could do Victorian blood and thunder with quite the same glee as Tod Slaughter, who played the Demon Barber in 1936, and who romped with exuberant relish through so many late 19th/early 20th century stage plays and films?

outright maniac, stalking, Jack-the-Ripper-like, through dark streets, with the accompaniments of swirling cloak and sinister surgeon’s bag? Would it be over the top to have a chuckling, hand-washing Sweeney-Todd character? While acknowledging the irresistible Johnny Depp’s performance in that role, it has to be observed that nobody could do Victorian blood and thunder with quite the same glee as Tod Slaughter, who played the Demon Barber in 1936, and who romped with exuberant relish through so many late 19th/early 20th century stage plays and films?

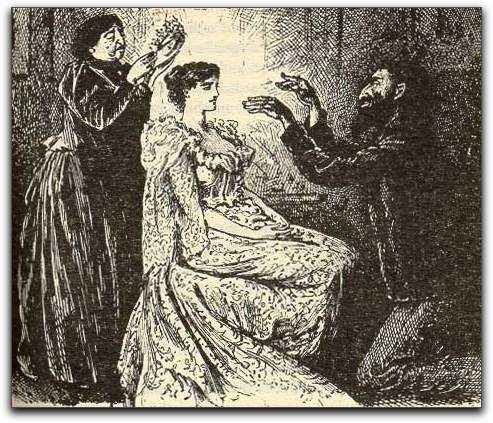

Ge orge du Maurier, creating Svengali, gave the world a mesmeric character, as well as a new word for the English language, and even a legal tactic – the ‘Svengali Defence’, in which a defendant claims to be a pawn in the scheme of an overpowering and influential criminal mastermind. It also gave actors from Beerbohm Tree to John Barrymore and Donald Wolfit the chance to flex their fruitier acting techniques. (It probably helped the sales of Trilby hats too, although that’s a frivolous side speculation).

orge du Maurier, creating Svengali, gave the world a mesmeric character, as well as a new word for the English language, and even a legal tactic – the ‘Svengali Defence’, in which a defendant claims to be a pawn in the scheme of an overpowering and influential criminal mastermind. It also gave actors from Beerbohm Tree to John Barrymore and Donald Wolfit the chance to flex their fruitier acting techniques. (It probably helped the sales of Trilby hats too, although that’s a frivolous side speculation).

As an alternative to Eastern European mesmerists or East End barbers with an innovative idea for meat pies, the villain might be given a more homely image. Perhaps he can credibly be portrayed as a mild-mannered gentleman, about whom shocked neighbours say that no one would ever have suspected him of such wickedness. He seemed so considerate, diligently looking after his house and his garden, even laying that beautiful patio… You wouldn’t have thought he would have bumped off seven people for the insurance money, or killed the golf club treasurer for the deposit account.

One of the interesting aspects of this part of characterisation is showing the multi-layered lives villains lead. They aren’t always stalking hapless heroines through fog-bound Victorian London, or laying macabre traps for unwary widows with  useful fortunes. As well as those activities, they have to do ordinary things like collecting the dry-cleaning or going to the dentist. Applying for mortgages, perhaps: ‘Occupation, sir? A doctor? Oh, well, Dr Crippen, we’re always happy to lend money to members of the medical profession…’ Or, possibly: ‘We’ll just get this house in Rillington Place surveyed before you buy it, Mr Christie…’

useful fortunes. As well as those activities, they have to do ordinary things like collecting the dry-cleaning or going to the dentist. Applying for mortgages, perhaps: ‘Occupation, sir? A doctor? Oh, well, Dr Crippen, we’re always happy to lend money to members of the medical profession…’ Or, possibly: ‘We’ll just get this house in Rillington Place surveyed before you buy it, Mr Christie…’

The Gilbert & Sullivan verse from the Pirates of Penzance, sums it up quite neatly:

‘When the enterprising burglar’s not a-burgling/When the cut-throat isn’t occupied in crime/He loves to hear the little brook a-gurgling/ And listen to the merry village chime.’

As for the villain’s appearance, it can be entirely ordinary. You don’t have to give him eyebrows that meet in the middle or hair that grows to a peak on his forehead – or allot to the villainess the kind of pallor and brooding eyes associated with Morticia Addams, or the black hair and rearing horns favoured by Maleficent. On the other hand, a disfigurement does not necessarily detract from a certain dark charm – as Gaston Le Roux proved in creating his famous Phantom, a character he apparently based on the discovery of a corpse found in the foundations of the Paris Opera House.

Generally, the villain, no matter how charismatic or multi-layered, does have to be given his or her just desserts in the final chapter. It’s not exactly a convention that has to be observed, but it’s expected. Even if he/she isn’t tried and sentenced in the conventional manner, some kind  of fate has to be meted out. This might cheat an author of writing a taut courtroom/prison cell scene, but it does open up a beautiful range of dramatic possibilities, including sending the culprit tumbling over the Reichenbach Falls, being submerged beneath the Paris Opera House, spontaneously combusting like Krook in Bleak House, or falling into the jaws of a crocodile as Captain Hook memorably did in Peter Pan.

of fate has to be meted out. This might cheat an author of writing a taut courtroom/prison cell scene, but it does open up a beautiful range of dramatic possibilities, including sending the culprit tumbling over the Reichenbach Falls, being submerged beneath the Paris Opera House, spontaneously combusting like Krook in Bleak House, or falling into the jaws of a crocodile as Captain Hook memorably did in Peter Pan.

And again, Gilbert & Sullivan knew about appropriate fates, when they caused no less a person than the Emperor of Japan to vow, in The Mikado, that he would always let the punishment fit the crime.

That said, it must be admitted that before writing the closing scene, the monster might escape his Frankenstein, to the extent that around Page 200 you realise you’re making notes for a sequel in which the miscreant will return like a giant refreshed. On that score, though, it’s probably as well to resist the temptation to allot to your villain one of the hammy Hammer finale lines. Fu Manchu, in the last reel of most of the film versions of Sax Rohmer’s books, comes to mind here – he had the way of raising an elegant hand, and portentously announcing that, ‘The world will hear from me again.’ Thus paving the way for sequels by the cartload. But perhaps the palm for a really indelible last line should go to Hannibal Lector. Who can forget him strolling into the sunset of the last page/reel of film in Silence of the Lambs, informing his protagonist that he’s about to have an old friend for dinner…?

Shakespeare (of course), sums it up neatly in Gloucester’s words in Richard III:

‘…thus I clothe my naked villainy with odd old ends stol’n forth of holy writ… And seem a saint when most I play the devil.’