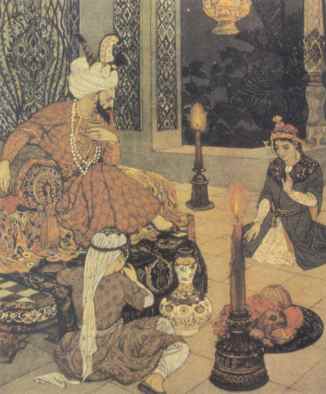

There are many theories as to when story-telling actually began. In the old Arabian legends, Scheherazade was allowed to live for the following day if she told an entertaining story that night. Which is singing for your supper with a vengeance.

Our prehistoric ancestors spun tales about what might lie in the darkness beyond their cave fires. They were a bit restricted, of course, not having pens or paper or ink, and probably limited when it came to actual speech, as well, but they could paint their stories with considerable clarity and drama, as innumerable cave paintings prove. They probably didn’t go a huge bundle on chick-lit – describing a candle-lit dinner wouldn’t have met with much credibility when most people were living in hollowed-out rocks, and hoarding their fire-making equipment to keep prowling predators at bay – but they would have been able to tell many a gripping yarn when it came to chase sequences. ‘And the dinosaur ran for its life, with the entire clan chasing it…’

When James Frazer was collecting material for the Golden Bough, he was very generous with the giving out of fire-water to the various tribes he talked to. And the tribes, liking the fire-water – as who would not? – apparently used to go away and think up tales to tell him, to get more of the stuff. Which begs the question as to how far a legend can be trusted.

There’s also the existence of the quest, a plot structure found almost everywhere on earth from the earliest recorded times. It’s a universally-known theme: a character leaves the safety of his home, and whether he’s searching for the Holy Grail, a Golden Fleece, or the ‘One Ring that rules them all,’ he has to endure a dangerous journey into forbidden territories (allowing the narrator to conjure up marvellous and often fantastical settings), and usually defeat a few enemies along the way. Often there’s a period of extreme hardship to be endured as Sir Gareth found in the Knights of the Round Table saga, when he was made to work as what Thomas Malory calls a ‘lowly kitchen boy’ in Camelot, before achieving recognition, honour, and – of course – winning the lady of the castle.

A similar period of adversity is accorded to the heroine best known as Cinderella – a story which apparently pre-dates Grimm and Disney by almost a thousand years, and seems to have made its first appearance in a Chinese book written around 850 A.D. In that version, Cinderella is called Yeh-hsien, and her ball gown is a cloak of kingfisher feathers, although the shoe motif remains, with gold shoes replacing the glass slippers – which  probably proves that a girl in any era will suffer a good deal to get a decent pair of shoes, and may go some way to explaining the shocking cost of today’s Christian Louboutins.

probably proves that a girl in any era will suffer a good deal to get a decent pair of shoes, and may go some way to explaining the shocking cost of today’s Christian Louboutins.

In 1930 with television still in its infancy, there was widespread horror at a project to dramatise a novella for TV. The title was The Man with a Flower in His Mouth, and it was prophesied that the experiment would herald the end of the book – that the country would subside into a cultural wilderness and authors would become an endangered species.

It didn’t happen. Nowadays, authors and publishers will do anything to secure a TV deal for a book. As for digital publishing – according to some authorities, the success of that took the publishing world somewhat by surprise.

The art of story-telling goes on. It adapts and, as an art, it’s a survivor.

The people who spin the stories adapt as well. They, too, are survivors.